For over six centuries, a mysterious illustrated book has defied every attempt at translation.

Is it a lost language, an elaborate code, or an epic hoax?.

A Medieval Mystery found in Italy

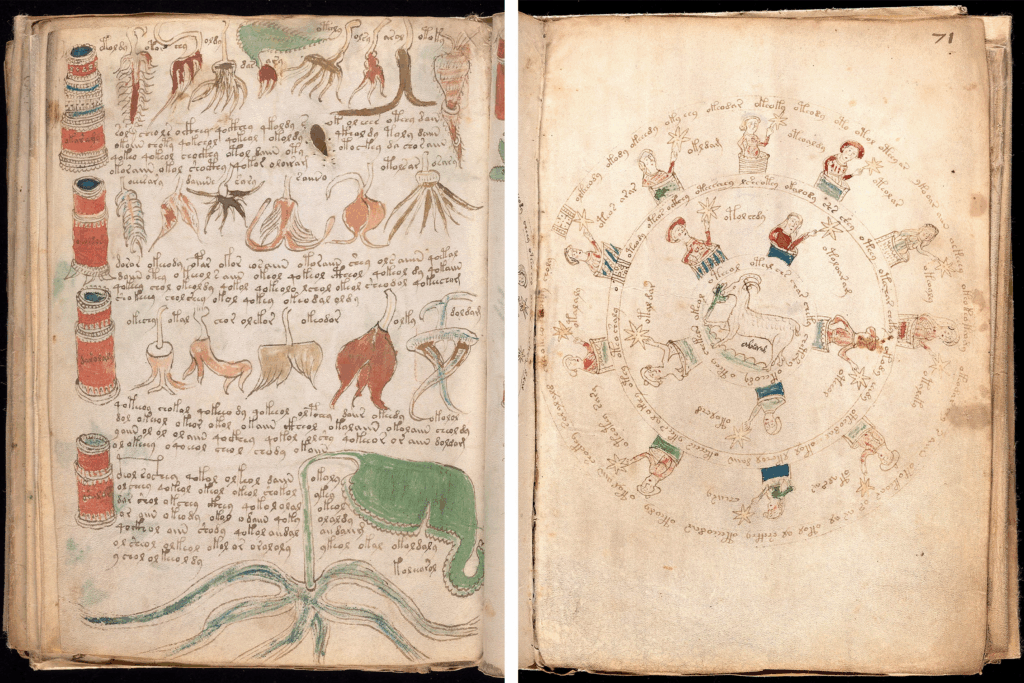

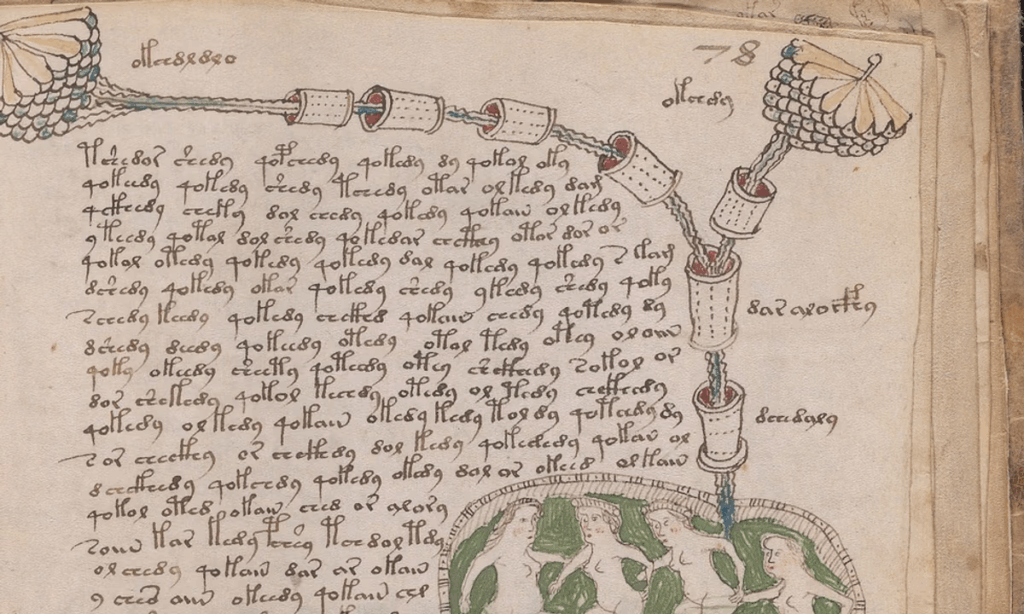

In 1912, a Polish antique book dealer named Wilfrid Voynich made an interesting discovery: an old vellum manuscript filled with graceful yet indecipherable script and colorful drawings of exotic plants, intricate astrological charts, and bathing nude figures.

Carbon dating later showed the book’s parchment dates to the early 15th century, meaning it was likely created in the 1400s.

Yet no one – not linguists, cryptographers, nor computers – has ever managed to read a single sentence of what’s now known as the Voynich Manuscript.

The text is written in an unknown writing system that scholars simply call “Voynichese.”

It doesn’t match any known human language, alphabet, or code.

A hoax?

Also no.

Statistical analysis shows the script isn’t random gibberish either – it follows patterns like a real language, just one completely alien to everyone who’s tried to decode it.

But what is it then?

The Voynich Manuscript resides today at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book Library in US, cataloged as “MS 408,” but it remains one-of-a-kind.

Roughly 240 pages long, it appears to be a collection with sections on botany, astronomy, biology, and perhaps pharmacy or recipes.

Almost every page features fantastical illustrations: drawings of unidentified plants with roots and leaves that don’t quite match any known species, zodiac symbols and star charts, and tiny nymph-like women immersed in tubs of green fluid, connected by strange plumbing-like tubes.

These images hint at herbal, alchemical, or astrological knowledge – but without understanding the text, their exact meaning is as cryptic as the spidery script itself.

It has captivated imaginations for over a century, creating an enduring allure that combines the thrill of historical discovery, and has been called by many “the world’s most mysterious book”.

Codebreakers vs. “The Impossible Book”

From the moment Voynich revealed the manuscript to the world, the race to decipher it was on.

Professional cryptographers, linguists, and enthusiastic amateurs alike have tried to crack its code.

And all have failed.

In fact, Yale’s curators report they still receive emails weekly from people claiming to have solved the manuscript, but so far no theory has held up under scrutiny.

Over the decades, the Voynich Manuscript earned a reputation as an almost cursed puzzle.

Unsolvable.

There’s even an academic joke that studying it can be “pure poison” for one’s scholarly career – because it’s so easy to get drawn in, make a bold claim, and then make a ridiculous mistake.

That hasn’t stopped generations of codebreakers from trying.

In 1921, a philosophy professor named William Newbold announced he had cracked the Voynich’s secret.

He claimed the manuscript was the work of a 13th-century friar (Roger Bacon), writing in a complex code: according to Newbold, each bizarre Voynich character concealed microscopic Latin letters that could only be seen under magnification. If true, this would mean the author had invented the microscope centuries early!

Unfortunately – and unsurprisingly – Newbold was mistaken.

Another scholar, John Manly, soon debunked this theory as wishful thinking, showing that Newbold’s “decipherment” was based on imagined shapes in the ink. Newbold’s attempt was one of the first of many Voynich decoding claims to be disproved.

During World War II and the Cold War era, some of the world’s top cryptanalysts turned their attention to the Voynich Manuscript.

William Friedman, a legendary American codebreaker who helped crack enemy codes during WWII, was fascinated by Voynich. He and a team of colleagues (including his equally brilliant wife, Elizebeth Friedman) pored over the manuscript’s text in the 1940s and 50s.

They even used early IBM punch-card machines to analyze letter frequencies – cutting-edge computing power for that time.

Yet despite their expertise in unraveling wartime ciphers, the Voynich’s contents eluded them.

Famously, Friedman never found the key, though he did coin the term “Voynichese” for the script.

To this day, even the National Security Agency’s library keeps a copy of the Voynich Manuscript as a training exercise and curiosity. It’s an unclassified puzzle perfect for testing new codebreaking techniques. A sandbox for cryptographic research, since no confidential messages are at stake.

Over the years, countless theories have bloomed and withered. Scholars and hobbyists have variously argued the Voynich Manuscript is:

- An Undeciphered Natural Language: perhaps a lost dialect or extinct language encoded in an original alphabet. Some have pointed to medieval Latin or German dialects written in cipher. Others suggest a completely lost language of central Europe. The challenge is that no clear evidence of any known language’s syntax or vocabulary has emerged so far.

- A Constructed Script for a Hoax or Fantasy: Could it be an elaborate hoax or a piece of creative fiction? One recent analysis proposed that the text might have been generated by a random process – essentially medieval gibberish that only looks like a real language. The researchers even outlined a method by which a 15th-century trickster could have algorithmically produced the Voynich’s weird word-like strings. If true, the manuscript might be a grand practical joke with no solution at all.

- A Cipher for Secret Information: Perhaps the Voynich is written in a real language that’s been tightly encoded or scrambled. This has been a leading idea for decades: maybe it’s a scientific or magical treatise deliberately enciphered to hide its knowledge. Yet despite applying every cipher-breaking trick in the book – from simple substitution codes to complex polyalphabetic ciphers – no one has found a convincing decrypt. The lack of known plaintext or context makes it fiendishly hard to verify any “solution.”

- An Unknown Script for Known Ideas: A twist on the cipher notion is that Voynichese might be an invented alphabet used to write a familiar language phonetically. For example, one team believes the manuscript is actually written in a form of medieval Turkish, just using a made-up alphabet. Others, like linguist Stephen Bax, tried identifying proper nouns (plant names, star names) in the text and thought they recognized terms like “Taurus” near a drawing of the bull constellation or the word for “coriander” next to a plant diagram. These hints were intriguing, but they haven’t unlocked a full translation.

Despite the flurry of ideas, none of these theories has achieved broad acceptance.

Every few years, someone will announce with fanfare that they’ve solved the Voynich Manuscript – only to be met with skepticism and rebuttals from the experts.

Just in the last couple of years, for instance, one academic claimed the Voynich was written in a “vulgar Latin dialect” using a unique shorthand system, while another published a paper arguing it’s a mix of languages he termed “proto-Romance”.

Both claims made headlines, but both were quickly challenged and debunked by linguists and cryptologists. In fact, one university had to retract its own press release about the “proto-Romance” solution after peer experts tore it apart.

It seems the Voynich Manuscript loves to humble even the boldest code-cracker.

Modern Tech and AI to the Rescue?

With today’s computing power, researchers can analyze the text in ways Voynich hunters of the past could only dream of.

Every character of the manuscript has been digitized.

Enabling statistical analysis of letter patterns and even the application of AI language-detection algorithms. These high-tech approaches have produced fascinating results – though not yet the ultimate answer.

On one side, computational studies have added evidence that the Voynich text has real structure.

For example, in 2013 a team of Brazilian and German scientists applied statistical physics methods to the manuscript’s gibberish-like words. They found hidden linguistic patterns consistent with actual languages, concluding that the text didn’t seem to be randomly generated nonsense.

In other words, there is something behind the madness – a signal in the noise – even if we can’t understand it. This supports the idea that the Voynich Manuscript encodes meaningful content, rather than being an elaborate hoax of random symbols.

In 2016, computer scientists Greg Kondrak and Bradley Hauer at the University of Alberta fed the Voynich text into an AI trained on dozens of languages.

The algorithm’s surprising verdict: the best statistical fit for the underlying language was Hebrew.

According to their hypothesis, the manuscript’s unknown script might be a cipher for Hebrew that includes anagrams or alphabet substitutions, yielding a jumbled mess that still retains some Hebrew-like patterns.

As a test, they used their AI to anagram one passage into Hebrew and claimed it could read (roughly) as a sentence about a “farmers’ wife… advising the priest”.

This made for exciting headlines – imagine, a computer finally cracks the Voynich! – but other scholars remained unconvinced.

The “Hebrew hypothesis,” like those before it, remains unproven and incomplete.

Meanwhile, an Turkish engineering duo (a father and son) have put forward a competing high-tech theory: they theorize Voynichese is actually a phonetic transcription of a medieval Turkic language, written in an invented alphabet.

And one recent statistical study in late 2020 used visual AI analysis on the characters, suggesting the script’s symbols cluster in patterns similar to known writing systems.

Each of these efforts draws significant interest – after all, who wouldn’t want the breakthrough on such an interesting mystery?

Yet so far, no AI or algorithm has conclusively solved it.

Why do so many people keep chasing this mystery?

The Voynich Manuscript sits at the perfect crossroads of history, mystery, and adventure.

It’s a real artifact from our past – you could literally hold it in your hands – yet it feels like something out of a fantasy novel.

There’s an almost romantic appeal to the image of a lone codebreaker or a modern AI finally yelling “Eureka!” and revealing the manuscript’s secrets. Each person who takes on the Voynich is, in a way, engaging in a grand puzzle that has defeated everyone before.

As medieval scholar Lisa Fagin Davis notes, it’s “the ultimate opportunity to prove [your] analytical skills” – a chance to beat the ultimate challenge.

For other researchers, it’s simply the thrill of the hunt: the journey of discovery, with twists, dead-ends, and the teasing hope of being the one to finally unlock a piece of the past.

In a world where information is often just a click away, this little book reminds us that there are still mysteries that resist easy answers – and that the journey of seeking knowledge can be just as rewarding as the destination.

For all of us puzzle-lovers and story-seekers, that’s a comforting thought.

Sources: The Yale Daily News, Undark Magazine, Live Science, Wikipedia, Beinecke Library archives.